Sermon for Sunday October 17, 2010 Swarthmore Presbyterian Church Swarthmore, PA “A New Covenant”

Sermon for Sunday October 17, 2010

Swarthmore Presbyterian Church

Swarthmore, PA

“A New Covenant”

Mark Braverman

Jeremiah 31:27-34

Genesis 32:22-31

Luke 18:1-8

It’s a joy to be in your midst and I want to thank Dick for the honor of preaching from his pulpit. You know, as a Jew who grew up in the synagogue, preaching from a prescribed set of scripture reading is very familiar territory. Every Sabbath we read a section from the Five Books of Moses – it’s a one-year cycle, we divided it into 52 portions – and a selection from prophets that is textually or thematically linked to the Pentateuch reading. But when I discovered the lectionary I was so delighted – what an embarrassment of riches for the preacher! There is the Old Testament — with a psalm as a bonus, and Gospels, and Epistles. And for me, especially – this you need to understand — growing up I was not supposed to read the New Testament, indeed even entering a church was out of the question – it was actually considered a dangerous place – such was the legacy of Europe. And so to bring the scriptures together into a whole is a miraculous coming together for me, a reestablishment of wholeness, a wholeness and coming together in faith, I submit, that is a matter of the utmost urgency to us today.

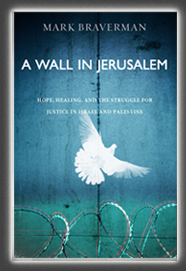

This theme of unity and wholeness is key in my personal journey. It is a story of understanding the walls that divide us and how to bring them down. I must tell you, as a Jew, living in this particular period of Jewish history, I feel that my people is facing a crisis, that we are in peril. A time in which we desperately need to look in the mirror, a time in which we are in urgent need of prophecy. And so today we have Jeremiah. Of all the prophets, Jeremiah does not mince words, he does not hold back, he lets you have it straight, as a prophet should. As he says in today’s reading, he is here to put our teeth on edge.

In chapter 17 Jeremiah, in a stunningly brief and graphic image, proclaims:

The sin of Judah is written with an iron pen; With a diamond point it is engraved upon the tablet of their heart and on the horns of their altars.

Jeremiah’s prophetic mission was to preach to Judah about, in Walter Brueggmann’s words, the end of the known world. And to proclaim, in the context of God’s lasting lovingness, the possibility, the inevitability, really, and the necessity of a new thing.

In today’s reading, the prophet announces

Behold, the days are coming, declares the LORD, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah. It will not be like the covenant that I made with their fathers on the day when I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt.

Know what is coming, says the prophet, and look straight in the face of the hard reality that confronts you, and be open to the new.

My own personal journey mirrors this kind of a process.

I was born in the United States in 1948 – the year of the declaration of the State of Israel. I was taught that a miracle – born of heroism and bravery – had blessed my generation. The State of Israel was not a mere historical event – it was redemption. In every generation, so goes the song we would sing every year at the Passover seder, tyrants — Pharaoh, Hitler, and, of course, Gamal Nasser—rise up to oppress us, and the Lord stretches out his hand to save us from annihilation. Jewish history was a story of struggle, exile, oppression, and slaughter that had culminated in a homeland. The suffering, the helplessness, was over.

The story of the birth of the State of Israel in which I was steeped, in which in fact the whole western world had been schooled, partook of this narrative. We have suffered, but because we have been selected by God for a special role in history by God, with the suffering comes the assurance of deliverance from oppression. The legacy of Europe that shaped my generation of Jews and the generations that followed is a sense of specialness, of separateness, and a kind of brittle sense of superiority and entitlement. So growing up Jewish was wonderful – but it also involved living behind a wall of protection, of self-preservation.

I embraced this narrative, I adopted this identity of specialness and separateness.

Until I saw the occupation.

I travelled to the occupied West Bank in 2006. When I saw the dispossession and oppression being perpetrated in my name, it broke my heart and what is more important it challenged my assumptions and beliefs. I saw the wall and the land grab, I saw the impact on the psyches and souls of my Jewish cousins manning those checkpoints. I learned about another 1948 narrative – that what we Jews call the War of Independence was for Palestinians the Nakba – the great catastrophe. I began to understand that the dispossession of three quarters of a million men, women and children to make way for the Jewish State, a crime of ethnic cleansing that continues to unfold to this day, was and is an essential part of my own story as a Jew today. Most important of all, I met the Palestinian people, recognized them as my brothers and sisters. I saw that they did not hate me. For me, the wall began to come down.

I realized that if my own people were going to survive, we had to transcend our sense of specialness and victim-tinged entitlement, a sensibility nourished for 2000 years that had now taken the form of political Zionism — the claim to the land as our particular inheritance and right. I realized that as a Jew I must consider hard the distinction between loving a land and claiming it as my birthright. When you claim a superior right to a territory shared by others, whether that claim is made on historical, religious or political grounds, you head straight for disaster. We Jews need to take a long hard look at our willingness to invoke the land clause of the covenant. Finally, I realized that the meaning of the Holocaust was not that we had to retreat behind walls of protection. To the contrary – the experience must lead us to a recognition of the universality of human suffering and our obligation to relieve it.

The events of the last few weeks in the unraveling of the so-called peace process in the Middle East should demonstrate to those who even until now have been holding on to the illusion of an Israeli leadership negotiating in good faith for a fair settlement with the Palestinians, and to those clinging to the fiction of the U.S. as an “honest broker” in these negotiations, it must demonstrate that even as we cry peace, peace, there is no peace. Instead, we contemplate the continuation of a political system under which the Palestinians live that can only be described as apartheid, and the prospect of continued conflict and increasing isolation in the world for Israelis — who feel increasingly confused, isolated and beleaguered. For me, as a Jew, this is sad, angering, and frightening.

When, in the summer of 2006, I stood before the 25-foot high barrier carving its way through East Jerusalem, I was filled with horror and shame. Yes, it was ugly and it was shameful, but it was not just that. I looked at that concrete obscenity and something else turned over inside me. I realized that this was the wall that I carried inside me. I saw it, and in seeing it I saw it come down.

Our reading from Genesis today is a story about a similar moment of truth, a similar life crisis.

It tells the story of the patriarch Jacob at midlife. A wealthy man with two wives, eleven children, and herds of livestock, he is facing the greatest crisis of his life: a confrontation with his brother Esau, from whom he had stolen their father’s blessing twenty years earlier. Jacob learns that Esau is approaching his camp with a force of four hundred. It is the dark night of the soul for the patriarch. His past has caught up with him, and he is afraid. Stubbornly and with remarkable endurance, Jacob struggles with a mysterious adversary throughout the night. At daybreak, the man begs Jacob to release him. Jacob believes that it is God with whom he has been wrestling, and that his own fortitude and agency has earned him legitimacy and power. “I have seen God face to face,” proclaims Jacob, as he, wounded from the struggle, limps off to meet his brother and his fate.

The lectionary reading cuts off here, but this is not the end of the story. In fact, this leaves us, I fear, with a distorted and flawed picture of the lesson of this remarkable encounter. We know who Jacob is fighting with on this dark night of his soul – it’s himself. He’s flawed, he has growing to do – that’s the meaning of the limp.

What do we Jews do about the tragic pass to which our homeland project has brought us? How long do we cling to the illusion that it is the other’s hatred of us that is the barrier to peace? When do we wrestle with this adversary of our own blindness, clinging to the myth, in Walter Wink’s words of redemptive violence, and open our eyes to the answer?

For here is the final lesson to be learned from the story of Jacob’s night of struggle: when, the next day, he meets Esau, it is a joyful reunion. Esau tearfully embraces him—all is forgiven. They are brothers, after all. And then Jacob says an astonishing thing to Esau: “I have seen thy face, as though I had seen the face of God” (33:10). Jacob had thought that he had encountered God the previous night—encountered God and prevailed. The next day, he realized that it was himself who he had met during the night: his own fears, his own self-involvement. The face of God that he had sought was waiting for him across the river. It was the face of his brother, whom he had wronged and who had already forgiven him. The answer to our dilemma as Jews today, our own dark night, is waiting, across the river, across the boundary of walls and defenses that we have built to protect ourselves from our own fears. It is our own brothers (and sisters) who are waiting for us.

We are facing a moment of truth. And it has to do – how much more simple can it get? — with recognizing our brother. Surely, as Americans, we all face this crisis.

And yet there is something else, another barrier to overcome, also common and also simple, and it is for all of us to overcome. How, in the midst of this frustration and worsening, how do we not lose heart, how do we keep our faith? The parable from Luke of the persistent widow comes to supply the simple answer. In the Bible the widow is the symbol for the social justice imperative. The widow is there to remind us of our responsibility for equal justice for all, especially for those with the least power in our society. Jesus brings this parable to remind us of the steadfastness of God’s love, in the face of, especially in the face of the most frustrating and unfair situations. Learn from the widow, he teaches us, learn from those with the most reason to give up in the face of unending and worsening injustice. Learn from those Palestinian mothers and fathers in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, who – despite the occupation open their stores in the morning and send their children off to school. From the farmers who harvest their olives and grapes as the noose of restrictions on movement tightens, and harassment from encroaching illegal settlements continues. From the Israeli teenagers saying no to army conscription or the decorated Israeli helicopter pilot refusing to fly missions over civilian areas and then joining the Jewish ship to break the blockade of Gaza. From the Palestinian Christians of Sabeel who tell us, we follow Jesus, a Palestinian Jew who lived under Roman occupation and who preached nonviolent resistance and love of your enemy. From the faith of Palestinian and Jewish families who have lost children to the conflict meeting together to share their grief and their commitment to peace, proclaiming that they refuse to be enemies. From the courage of an ecumenical group of Palestinian Christian clergy and social leaders who together create the Palestine Kairos statement, a prophetic document that states – our condition is horrible and getting worse. And yet we have hope because our faith requires it. We reach out, as Jesus tells us to, to our occupier in the spirit of love – live with us, in a just society, as God requires.

It is this kind of faith and persistence – originating from the churches and their leadership – that changed the political wind and brought an end to legalized racial discrimination in this country and the end of Apartheid in South Africa. The leaders of the NARC meeting in Ottawa Canada in 1982, confronted with their black and colored colleagues from South Africa, who refused to sit at the Lord’s supper with them because they could not do that at home, declared the church to be in status confessionis – that means no movement forward, no further church business until a situation that challenged the very foundation of their faith was corrected. We are not OK with God, these church leaders said, until this is remedied! And promptly threw out the SA churches from the worldwide church until this betrayal of the core of their faith was seen to. No deals, no negotiation, no peace process – nothing moves until this is fixed. The Reverend Martin Luther King sat in a jail cell in Birmingham Alabama and penned words on smuggled out scraps of paper that speak clearly to us across almost 50 years of human history. A letter in which he explained why the black men and women and children of America could no longer “wait” — as the white clergy who had appealed to him had beseeched — to desist from his campaign of direct action, and to rather work patiently through the laws of the land. In which he explained why unjust laws had to be resisted.

Most important, Reverend King issued a call to the church:

There was a time when the church was very powerful–in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society.

…the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century.

These words ring out to us today. When the history of this time is written, what side of history will our pastors, Rabbis and community leaders find themselves to have been on? The leaders are the key – Dick has made is decision about that – as have scores of others – I know many of them, have preached from their pulpits, met them in the Holy Land visiting the living stones of peacemakers, met the members of their congregations holding conferences, organizing classes, selling Palestinian products at Advent. The brave, stubborn, persistent people of the Presbyterian church who – God Bless them – go back into the fray year after year introducing overtures to their denomination to divest from companies profiting from the illegal occupation of Palestine.

I find myself saying to Christians who seek a devotional pilgrimage to the Holy Land: Yes! Go! Walk where Jesus walked! For, if you do go and – leaving the tourist trail, see what there is to be seen, you will not only walk where he walked but you will see what he saw. And then you will go back to your Bibles and understand the gospels as the record of a movement of social transformation and nonviolent resistance to the evil of empire. In a tragic and compelling parallel, this is what we see being played out today, in the Palestine of 2000 years later. What is happening today in the Holy Land is an indigenous population subjugated by a colonizing power. What we see today is an occupied people fighting for dignity, human rights, and justice. Just as Jesus, in the tradition of Jewish prophets from which he sprang, spoke truth to the power of the Jerusalem establishment of his time, just as he stood up for his own people, the Jews of his time – Palestinians — so are we all required to find ours voice to speak the truth, even when it hurts, in faithfulness to God’s plan. To bring about the Kingdom of God – which to Jesus was not the end of days, but in our day.

Two hundred new housing units approved for East Jerusalem just this past Friday. A loyalty oath to Israel as the state of the Jewish people approved by the Israeli cabinet last week. What do we say about this? Longtime Middle East diplomat Dennis Ross, working for our President, offering backchannel deals to the Israeli government, giving away yet more chunks of Palestine in exchange for meaningless concessions from Israel. How do we deal with the fact that this peace process is no peace at all? Jesus shows us clearly what to do, and he didn’t make it easy. Not for the priests, not for Herod, not for Pilate. The prophets did not show us the easy way. Elijah, in his time, did not design a peace process. When he confronted King Ahab over the killing of Naboth and the theft of his land, he did not sidle up to the monarch, put his arm around his shoulder and say, “Ahab, this doesn’t look so good. We need to work on your image — and we need to figure out a better way to get you what you want. Let me talk to the folks in Jezreel and see what kind of a deal I can get for you.” No – we know what Elijah said: “Have you murdered and also taken?” In the Hebrew, the question is asked in three, shattering words — followed by a short discourse on the consequences to follow.

No, they do not make it easy, but they make it clear. In the midst of suffering and oppression, hold on to your faith, do as your faith directs you.

So the church is at home here. This is the social justice agenda that permeates the global church – it’s not a hard call! Except for the interfaith issue. That makes it difficult. I know. I know what charges you open yourselves to when you dare to question the actions of the State of Israel. I know that it threatens relationships with Jewish friends, family members and organizations, bridges of understanding built up over years, on personal, professional, and institutional levels. But I say to you: do not let yourselves be held captive to our struggle. Do what your faith directs you to do, even if many of your Jewish brothers and sisters refuse, for the time being, to accompany you on this ministry. Have compassion for us, honor the painful process that we must go through as we begin to look in the mirror and confront the awful consequences of our nationalist project. But do not wait for us. Do not confuse the work of reconciling with the Jewish people and atoning for millennia of anti-Jewish doctrine and acts with the urgent work that now calls. Fighting anti-Semitism is and continues to be important work – as is the opposition to all forms of racism – and Christianity has a lot to answer for in that regard. But the urgent call today is the call to justice for Palestine– justice that will alone bring peace to both the Palestinian and the Israeli peoples. I say this to you today what I have said to many Christian groups, from the pulpit, in denominational assemblies considering proposals to divest from companies profiting from the occupation of Palestine – if you want to love and honor the Jewish people, then work, as faithful Christians, for justice in the Holy Land.

This is the new covenant. Jeremiah lived at a time the direst crisis and peril – a time when the people faced the destruction and loss of everything they had worked for. In his prophecy he laid out what the meaning of the hard times was. Listen to him, from chapter 2:

My people have changed their glory

For that which does not profit.

Be appalled, O heavens, at this;

be shocked, be utterly desolate, declares the LORD,

for my people have committed two evils:

they have forsaken me, the fountain of living waters,

and hewed out cisterns for themselves,

broken cisterns that can hold no water.

The days are coming, Jeremiah tells us, for a new covenant. And God is writing it on our hearts. What does he mean by that? It means that it will hurt, but that it will be an expression of the deepest love there is. God writes on our hearts in the witness we make when we contemplate the checkpoints of Bethlehem, the rubble of Gaza, the deadened look in the eyes of my Jewish cousins manning those checkpoints, humiliating their Palestinian cousins in their homes and villages, the condition of their hearts as they return to their families from their bombing runs over defenseless Gaza.

This is the new covenant that calls to us. To break down the walls of separation, mistrust, fear.

We live in a world which, like that faced by Jeremiah and then 600 years later by Jesus, gives us every reason to hunker down in our bubble of prosperity, to say we can do nothing about the juggernaut of globalization that rapaciously exploits 90% of the world’s population in order to drape the remaining 10% in luxury and to feed a pursuit of material possession and sensual stimulation. We live in a world which encourages us to define ourselves according to how different we are from others – from other cultures, other countries, other faiths. We live in a world which prompts us to be full of fear, to hold on, and to close down, rather than to let go and open up. We live in a world that is tottering on the brink.

This then is our prayer this day, Lord of Creation: write on our hearts. Put your law within us, grant us the persistence and the courage of our sisters and brothers who live under the boot of oppression. Open our hearts so that, like the prophets and like Jesus before us, and like the prophets who still emerge to lead us today, we may do your will.

Amen