Which Side are We On? The Persistent Widow. Last Sunday of Pentecost, November 21, 2011

Sermon offered at St. John’s Episcopal Church Georgetown, Washington DC

Last Sunday after Pentecost

November 21, 2010

Mark Braverman

Jeremiah 23:1-6

Luke 23:33-43

Good morning! It’s a joy and a privilege to be with you this morning, and I want to thank Father Albert for the honor of preaching from this pulpit. It’s an important Sunday, pivotal as the last Sunday of the liturgical year. We prepare to enter the season of Advent — a time when we commemorate and contemplate an event that changed and shaped history. A time of kairos – Greek for a moment which presents the opportunity for fundamental change in human affairs. And as we gather this morning we are at such a time in history – we are called, and we are challenged. And, blessedly, we have the texts to guide us.

A word of explanation – I was asked after the 9AM service, as I sometimes am, whether I was a Jew or a Christian, had I converted? I know that the appearance of a Jew preaching from the Episcopal Lectionary on Sunday morning, and talking about Jesus in the way that you will hear me talking, can cause some confusion – among Christians as well as Jews. I am a faithful and proud Jew – and if my words cause confusion, this may not be a bad thing. The times require us from the Christian and Jewish communities – as well as Muslims – to struggle with how our faith traditions can meet the challenges of our time. It is desperately urgent that we connect with the fundamentals that unite us, rather than divide us. Today, some confusion is good as we push against, to use Paul’s words in his letter to the Ephesians, the walls that have divided us.

As a Jew who grew up in the synagogue, preaching from a prescribed set of scripture reading is very familiar territory. Every Sabbath we read a section from the Five Books of Moses – it’s a one-year cycle, we divided it into 52 portions – and a selection from the prophets. But when I discovered the lectionary I was so delighted – what an embarrassment of riches for the preacher! There is the Old Testament — with a psalm as a bonus, and Gospels, and Epistles. And for me, especially – this you need to understand — growing up I was not supposed to read the New Testament, and talk about Jesus was out of bounds. Even walking into a church was out of the question – it was actually considered a dangerous place – such was the legacy of Europe. And so to bring the scriptures together into a whole is a miraculous coming together for me, a wholeness and coming together in faith, I submit, that is a matter of the utmost urgency to us today.

Our first text is from the prophet Jeremiah, and, in typical Jeremiah style, it is not easy going. It is a warning, a calling to account. And he is talking to the leaders:

Woe to the shepherds who have scattered my flock, cries the prophet! The shepherd is the Biblical symbol for the leader, the true guide. If you are to lead your people, the prophet is telling us, you have to be more than a politician – as a King, you are responsible to God, you derive your power and authority from something higher. In this case, it is the political leaders who are responsible for the disaster of the destruction of Jerusalem and for the Babylonian exile.

The kings, says Jeremiah, have made offerings to other Gods – idols. They have worshipped the works of their own hands. My people, he charges, have changed their glory for something that does not profit. They have forsaken me, a fountain of living water, they have dug cisterns for themselves, cracked cisterns that hold no water.

Walter Brueggemann, the great Christian Old Testament scholar, writes a great deal on Jeremiah, relating the prophet’s message directly to our own times. After the 9/11 attacks Brueggemann looked hard at our reaction to the attacks and wondered what it said about how we saw ourselves as Americans in the broader arena of the world. Did we, asks Brueggemann, take the attacks as a wake up call about our own actions on the world stage? Or did we, secure in our goodness and the rightness of all our actions all the time, close our hearts and minds to the anger and suffering of others and embark on a course that would take us into a spiral of violence?

How many of you may have read irreverent columnist Matt Miller in yesterday’s Washington Post? He writes:

“Does anyone else think there’s something a little insecure about a country that requires its politicians to constantly declare how exceptional it is? A populace in need of this much reassurance may be the surest sign of looming national decline. ‘Americans believe with all their heart,’ said Marco Rubio upon winning his Senate race, ‘that the United States of America is simply the single greatest nation in all of human history, a place without equal in the history of all of mankind.’ Rubio described his Senate race as ‘a referendum on our identity,’ adding that “this race forces us to answer a very simple question,’ he said. ‘Do we want our country to continue to be exceptional, or are we prepared for it to become just like everyone else?’”

And then the column gets interesting.

“As a Jew, (Miller continues), I’m familiar with this issue in another context. According to the Torah, Jews are said to be “the chosen people.” Though this was a relatively affirming thing to be when you’re a kid in Sunday school – who wouldn’t want to be part of the club chosen by the Man Upstairs, after all? – as an adult, I’ve never taken it seriously. With all due respect to Jews who take this notion literally, it’s always struck me as presumptuous, if not offensive.”

And, I would add, dangerous.

I’ll get back to this issue of the Jewish people today. But let’s stay with Jeremiah for a moment.

After laying out in the starkest terms how Judah has gone wrong, Jeremiah calls for a new beginning – that’s the prophecy of a new branch, the new King, the new ruler. In these stirring words, he prophecies:

I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land. In his days Judah will be saved and Israel will live in safety. And this is the name by which he will be called: “The LORD is our righteousness.”

The Lord is our righteousness – as a nation, we will conduct our personal and collective lives in accordance with universal principles of justice and compassion. But this, in the prophetic vision, cannot come about until the people take a hard, long look in the mirror, realize how they have gone wrong, take responsibility for it. Only then is there the possibility of a new beginning.

Now in the Christian lens, this new beginning, this sought-after future time, is the Kingdom of God that Jesus came to proclaim. The strong hint here is the reference to the House of David. And this is right – Jesus is fully in the prophetic tradition. And, in that same prophetic tradition, Jesus does not imply that this comes about simply by fiat, by some act of God to bring about this change. Follow me, says Jesus, follow my teachings and my example. My father has sent me to you to bring this news to you, and to send you out to bring this news to the world, which means to actively bring about the Kingdom by acting, in the world, in accordance with God’s plan of love, compassion, and social justice. Liberation theologian Walter Wink writes about Jesus’ statement, My Kingdom is not of this world. Wink points out that in the gospel of John the Greek word for “world” is kosmos – which translates as order or system. In the Gospel accounts (Mark 13:2, Matthew 24:2), Jesus stands before the Temple and says: “Not one stone will be left upon another!” Translation: this old order is over. And in the Gospel of John (John 2:21), when Jesus says “Destroy this Temple and in three days I will raise it up,” the narrator, just to make sure we get the theology right, explains: “He spoke of the temple of his body.” Body of Christ: one body – mankind made one, whole, united in one spiritual community. This world, Jesus is saying, this system of empire which seeks only to increase its own power and reach at the expense of communities, families, human health and dignity, this Empire that tears at the fabric of society, destroying compassion between people and the bedrock of social justice, administered, not compassionately in the marketplaces and the gates of the city but arbitrarily and cruelly in the halls of power, this world order will give over to the Kingdom of God – something completely different.

Jesus’ vision of the Kingdom of God dispenses, finally, with the concept of God’s indwelling in the land, of a particular location as the place where God is to be worshiped. In the Christian vision, the idea of the physical land as a clause in the covenant disappears. In Jesus’ Kingdom of God, both the land and the people lose their specificity and exclusivity. Temple — gone. God dwelling in one place — over. And, most important, Jesus’ Kingdom takes the next step – it jettisons the special people concept. The special privilege of one family/tribe/nation that has the right to displace, conquer or oppress another people is done away with for good.

Here is where Jewish exceptionalism is eclipsed. And, by the way, so is our own American exceptionalism, the idea that our way, the Right Way, must be imposed by economic and military might. Exceptionalism is very much in the American DNA – the Puritans set that out clearly – a city on a Hill, Manifest Destiny, God is on our side and we have the right to sweep away anyone in our path. The Puritans were wrong. The displacement of indigenous peoples is not God’s will, it is not God’s plan.

And so today, in our own urgent historical context, it is essential that we Jews – and Christians as well, revisit this fundamental issue of theology and faith.

Today, we Jews have, again lost track of this fundamental truth in our pursuit of empowerment and security. It has put us in peril, a peril as deep and serious as what faced us in Jeremiah’s time.

As a Jew born in post-World War II America, I was raised in a potent combination of Rabbinic Judaism and political Zionism. I grew up immersed in the Zionist narrative. I was taught that a miracle – born of heroism and bravery – had blessed my generation. The State of Israel was not a mere historical event – it was redemption from millennia of marginalization, demonization, and murderous violence. The legacy of this history was a sense of separateness – a collective identity of brittle superiority for having survived, despite the effort, “in every age” – so reads the Passover liturgy — to eradicate us. The ideology and mythology of the birth of the State of Israel partook of this legacy of separateness, vulnerability, and specialness. I embraced it.

Until I saw the occupation.

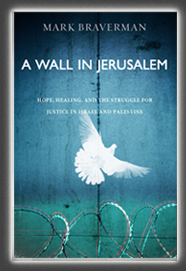

When I saw the dispossession and oppression being perpetrated in my name, it broke my heart and what is more important it challenged my assumptions and beliefs. I saw the wall and the land grab, I saw the impact on the psyches and souls of my Jewish cousins manning those checkpoints. I learned about another narrative, the Nakba, and understood that the dispossession of three quarters of a million men, women and children to make way for the Jewish State, a crime that continues to this day, was an essential part of my own story as a Jew. I saw how the Nazi Holocaust was being used as political indoctrination and as justification for this project, which was ongoing. I realized that the meaning of the Holocaust was not that we had to retreat behind walls of protection but rather to open our hearts to the universality of human suffering and our obligation to relieve it. But most of all, I met the Palestinian people, recognized them as my brothers and sisters.

I realized that to feel outrage toward the actions of my own people was the most Jewish thing I had ever felt, and that working for justice in Palestine was the most Jewish thing I could do.

It is important to us as Americans to look reality in the face here and to take responsibility for our own government’s complicity in this disaster. The diplomatic events of the past 10 months, as the U.S. tries in vain to bring about a peace deal in Israel and Palestine, reveal that the assumptions we have been operating under are myths — pure fantasy. It is the myth of an Israeli government committed to a just, fair peace deal with the Palestinians. It is the blatant lie of the U.S. as an honest broker to the so-called peace process when in fact the U.S. is acting, as it always has, as Israel’s banker and Israel’s lawyer on the world stage. In fact, the policies of Israel, which are to continue the annexation and colonization of Palestine, and the policy of the U.S., which is to allow this to continue without brakes, and with our massive financial and diplomatic support, has built a political system which South Africans who have gone to see it have not only described as Apartheid, but worse than the Apartheid system that plagued their land for half a century. And when politics fail, as Sojourners founder Jim Wallis says, broad grassroots movements arise to change the political wind and bring about the required change. And the movement that will accomplish this change bears strong similarities to the movements that brought about an end to legalized racism in the U.S., and to Apartheid in South Africa. And in both cases these movements arose in the churches and it was the churches that provided the leadership and the energy to bring about their success.

The church is called.

The church is called to respond to this urgent situation, to take a stand against it. And the church has been here before.

It was here in 1934 in Barmen, German when a group of pastors split off from the Nazi-sanctioned Reichskirche and declared themselves the German Confessing Church. It was here in 1982 in Ottawa, Canada when the World Alliance of Reformed Churches declared itself in status confessionis and suspended the South African member churches for their active complicity with Apartheid. The church was here in a jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963 where the Reverend Martin Luther King, arrested for civil disobedience, scribbled a letter on scraps of paper smuggled out by his friends. Recall the context. The writers of “A Call to Unity” — eight white pastors – had entreated Rev. King to end the demonstrations, boycotts and sit ins, recommending instead that African Americans engage in local negotiations and use the courts to seek the human rights that were denied them. Let us work through channels, they said. Let’s have a “peace process.”

To which he responded: we cannot wait. This is the right course of action for our churches, for our society, and for our leaders. This is what our Christian faith requires.

We are witnesses to the founding and growth of a civil society movement to delegitimize Israeli Apartheid. Politics have failed to bring about the required change. Indeed, the political process – here and in Israel — supports the evil. And when politics fail, as Sojourners founder Jim Wallis says, broad grassroots movements arise to change the political wind and bring about the required change.

So the church is at home here. This is the social justice agenda that permeates the global church – it’s not a hard call! Except for the interfaith issue. That makes it difficult. I know. I know what charges you open yourselves to when you dare to question the actions of the State of Israel – the worst charge a Christian can be subjected to – anti-Semite. Even to have it implied is the biggest club that can be wielded. I know that even raising the issue threatens relationships with Jewish friends, family members and organizations, bridges of understanding built up over years, on personal, professional, and institutional levels. But I say to you: do not let yourselves be held captive to our struggle. Do what your faith directs you to do, even if many of your Jewish brothers and sisters refuse, for the time being, to accompany you on this ministry. But do not wait for us. Have compassion for us, honor the painful process that we must go through as we begin to look in the mirror and confront the awful consequences of our nationalist project. But do not confuse the faithful Christian project to reconcile with the Jewish people for centuries of anti-Semitism, with the urgent call to work for justice in Palestine, justice that alone will bring peace to both peoples – the Palestinians and the Jews.

Listen to Martin Luther King’s call, from the Birmingham jail letter:

There was a time when the church was very powerful–in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society.

…the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the 20th century.

These words call out to us today. When the history of this time is written, what side of history will our pastors, Rabbis and community leaders find themselves to have been on? Your own Father Albert has made his decision about that – as have scores of others – I know many of them, have preached from their pulpits, met them in the Holy Land visiting the living stones of peacemakers, met the members of their congregations holding conferences, organizing classes, selling Palestinian products at Advent. I have met and worked with the brave, stubborn, persistent people of the American churches who – God Bless them – go back into the fray year after year introducing overtures to their denominations to divest from companies profiting from the illegal occupation of Palestine, or boycotting goods produced in the illegal settlements that are taking Palestinian land and often violently disrupting the life of Palestinian farmers, and villagers. You did it before – you declared Apartheid in South Africa a heresy – and now the Christian leaders in the Holy Land are crying out to the global church for help. Read the Palestine Kairos statement, a prophetic document that states: Our condition is horrible and getting worse. And yet we have hope because our faith requires it. We reach out, as Jesus tells us to, to our occupier in the spirit of love – live with us, in a just society, as God requires.

How, in the midst of this frustration and worsening, how do we not lose heart, how do we keep our faith? The parable from Luke of the persistent widow comes to supply the simple answer. In the Bible the widow is the symbol for the social justice imperative. The widow is there to remind us of our responsibility for equal justice for all, especially for those with the least power in our society. Jesus brings this parable to remind us of the steadfastness of God’s love, in the face of, especially in the face of the most frustrating and unfair situations. Learn from the widow, he teaches us, learn from those with the most reason to give up in the face of unending and worsening injustice. Learn from those Palestinian mothers and fathers in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, who – despite the occupation open their stores in the morning and send their children off to school. Learn from the farmers who harvest their olives and grapes as the noose of restrictions on movement tightens, and harassment from encroaching illegal settlements continues. From the Israeli teenagers saying no to army conscription or the decorated Israeli helicopter pilot refusing to fly missions over civilian areas and then joining the Jewish ship to break the blockade of Gaza. From the Palestinian Christians of Sabeel who tell us: we follow Jesus, a Palestinian Jew who lived under Roman occupation and who preached nonviolent resistance and love of your enemy. From the faith of Palestinian and Jewish families who have lost children to the conflict meeting together to share their grief and their commitment to peace, proclaiming that they refuse to be enemies.

Which side are we on? Like Jesus, in the hour of his extremity, contemplating the two men crucified with him, one, as the Gospel reading today tells us, on his right side and one on his left, representing two examples of humanity, a fundamental choice faces us at this critical juncture of history. One of the criminals mocks Jesus, in doing so revealing a profound failure to understand who Jesus was, what he had come to show us. In contrast, the man on his other side simply acknowledges the divine, earth shattering event that is taking place, and that the reason for his own suffering was his own responsibility. And we know, as Jesus tells us in this passage, which one gains the Kingdom. And that Kingdom is here – on earth, in the shape of the world that we work to create, here, on earth.

Let us pray.

May it be your will that we will hear your call, understand your sacrifice, and be on the right side of the history it is ours to create.

Amen