Can These Bones Live? Day of Pentecost, Iona Abbey, Isle of Iona, Sunday, May 27, 2012

Can These Bones Live?

Day of Pentecost

Iona Abbey

Sunday, May 27, 2012

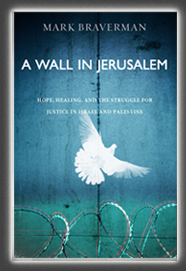

Mark Braverman

Acts 2:1-21

Ezekiel 37:1-14

It’s a joy to be in your midst and I want to thank the Iona community for the honor of preaching from this pulpit. You know, as a Jew who grew up in the synagogue, preaching from a prescribed set of scripture readings is familiar territory. Every Sabbath we read a section from the Torah starting from Genesis and ending in Deuteronomy– it’s a one-year cycle, 52 portions. But when I discovered the lectionary I was so delighted – what an embarrassment of riches for the preacher! There is the Old Testament — with a psalm as a bonus, and Gospels, and Epistles. And for me, especially – this you need to understand — growing up I was not supposed to read the New Testament, indeed even entering a church was a questionable if not dangerous act, such was the painful legacy of our shared history. And so to bring the scriptures together into one whole is a miracle for me, a wall coming down. And walls coming down is the topic of today’s preaching.

Pentecost, of course, is the Jewish festival of Shavuot – Shavuot means, literally, weeks — 7 weeks to be precise — after Passover, and this, we must assume, is what the disciples were doing gathered in Jerusalem that day. We have the unique phenomenon here of Christianity having preserved the name of the original Jewish festival, and I think this is right, because the themes of the two are remarkably linked. The Jewish festival commemorates the giving of the Law on Sinai — God descending on to the mountain, Moses going up to get the law, and the people – ultimately, after a terrible but highly instructive false start – receiving it. There are Jewish legends about this festival. I remember as a child keeping myself awake as long as possible on the eve of Shavuot because it was told that on this night only, the heavens, for one brief moment, would open.

But as important as they are, I don’t want to talk so much about convergences, rather about departures, differences, revolutionary developments — moments – like Sinai, and like the coming of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost, when everything changes, when history turns. To get to Pentecost, we count – 7 weeks and a day – that is chronos, linear time. But Sinai and Pentecost are not seen in linear, chronological time — they are kairos events – times that shatter our human counting of hours and minutes and weeks and years, times that reshape human history, times that challenge our assumptions and the established social and political order itself. A Kairos is, in the words of Robert McAfee Brown, a time when “God offers a new set of possibilities and we have to accept or decline.”

Kairos presents what a friend once described to me as a case of “insurmountable opportunity.” Even when – and usually this is the case – the objective may be clear enough but the path to follow is uncertain, full of hazards, uncharted, you must go. We call to mind George MacLeod’s statement: “Christians are explorers, not mapmakers.”

To understand what happened on that particular Pentecost, we need to go back one chapter prior to our reading for today, to the very opening of Acts. It is 40 days past Easter. Jesus, having appeared on a number of occasions to the disciples, has told them not to leave Jerusalem, that they must wait just a few days for the fulfillment of the promise of the Father. In typical fashion, Jesus doesn’t spend a lot of words explaining the why or the how of this. He says only this: that John had baptized with water; but that they will be baptized in the Holy Spirit. The disciples, as usual, are clueless. More than clueless — they get it completely wrong. As they have so many times before, they proceed to ask the wrong question, a question that reveals that they still do not understand what Jesus has been talking about for the three and a half years of his ministry, even now, even after Easter. Is this the time, they ask him, is it now Lord, that you will restore the kingdom to Israel? Even now, they do not comprehend what is meant by the Kingdom of God. They think it is about an earthly kingdom.

And so, at the close of this first chapter, we, like the disciples, are waiting to find out what it means to receive Power, what happens when the Holy Spirit comes upon us. Jesus gives them, and us, a strong hint, and it is the very last thing he says before he ascends to heaven: the time will come, he tells them, when indeed you will leave Jerusalem – “you will be my witnesses, not only in Jerusalem, but to all the land of Judea and Samaria,” but you will not stop there – it is to the ends of the earth that you must go!

This is the heart of the message of Pentecost.

After a brief piece of business involving the election of the now missing twelfth apostle, we find ourselves in chapter two, on the day of Pentecost. And the power from the Holy Spirit that Jesus had predicted arrives, but perhaps not in the way expected. It arrives not as a gentle bird of peace, not in a voice from heaven saying this is my beloved son, but as violent winds and tongues – tongues! — of fire that confer the ability to speak in all the languages of the known world! This is the power that came to the disciples. It was not about restoring the kingdom to Israel. It was not a restoration at all, not a return to a former state of glory or stability, not that kind of power. It is something completely new. From the kingdom of Israel we have moved to the ends of the earth – all places, all peoples, all humanity, all the earth. And speaking in the native language of each – in other words, in a common language.

Contrast this astonishing story with the descriptions of God coming to humankind that precede it in the scriptures. In the book of Genesis God speaks to Abraham, instructing him to travel to a specific land, which will be given as a possession to him and his descendants, along with the promise of wealth, progeny and blessing. The promise is reiterated to his grandson Jacob in the striking dream of the ladder reaching from heaven to – again — the land, the very land upon which he stands. And then of course at Sinai, when God is clearly depicted as descending upon a mountain. Contrast this with what we have here in the Pentecost story.

Pentecost tells a story, and the story is clear: it is the story of what humankind must now do if we are to survive, if we are to be with God. It is the movement away from possession of territory and toward the honoring of the entire earth, the movement from the particular to the universal. It is about what land means, to what use it is to be put. Make no mistake, these themes are contained in the Torah and the prophets, the building blocks are there and the prophets in particular strain toward it. But it is in the tongues and fire of Pentecost that the transition is now complete. Pentecost is the story of contrasts, between “when will you restore the Kingdom of Israel” and the power bestowed by the Holy Spirit to be my witnesses unto the ends of the earth.

In my own journey as a Jew born in the years immediately following World War II and within a month of the establishment of the State of Israel I have lived that contrast. Growing up, I was taught that a miracle had blessed my generation. The State of Israel was redemption from 2000 years of suffering and slaughter. In every generation, so goes the Passover liturgy, tyrants rise up to annihilate us, and the Lord God saves us from their hands. Jewish history was a story of struggle, exile, oppression, and slaughter that had now culminated, at last, in a homeland. We had been, literally, redeemed. The suffering and the helplessness were over.

The story of the birth of the State of Israel in which I was steeped, in which in fact the whole western world has been schooled, partook of this narrative. The legacy of Europe that shaped my generation of western Jews and the generations that followed was a sense of specialness, separateness, and entitlement. Growing up Jewish was wonderful – but it also involved living behind a wall of self-preservation, vulnerability, and a kind of brittle exclusivity.

I embraced this narrative, I adopted this identity. I carried that wall inside myself.

Until I witnessed the occupation of Palestine. When I saw the dispossession and oppression being perpetrated in my name, it broke my heart and it challenged my assumptions and beliefs. I learned about another narrative, the Nakba, in Arabic, “catastrophe,” the dispossession of three quarters of a million men, women and children to make way for the Jewish State. Most important, I met the Palestinian people and recognized them as my brothers and sisters. For me, the wall came down.

I realized that if my own people were going to survive, we had to transcend our sense of specialness and victim-tinged entitlement, a sense incubated for 2000 years that had now taken the form of political Zionism — the claim to the land as our particular inheritance and birthright.

Which brings us to our second reading, from the prophet Ezekiel, the well-known vision of the valley of the dry bones.

The connection between this and the reading from Acts seems clear: God comes in strong wind, and something changes dramatically. But how different this is.

The prophet Ezekiel, a member of the priestly class who had been exiled with the elite of the population to Babylonia, depicts his people in total despair: “Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.”

“Can these bones live?” God asks Ezekiel rhetorically, and then in answer commands him: “Prophesy to these bones, and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live.”

And what is this rebirth, this redemption from loss and exile? How does the Spirit of the Lord come to the people? It is, literally, in a restoration of the Kingdom of Israel – a return to the land, a rebuilding of the Temple. “I will bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel.”

It is 2006. I am visiting Israel and the Israeli occupied West Bank, and on this particular day I stand at the entrance Yad Vashem, the State of Israel’s national museum commemorating the Nazi Holocaust. As I enter the grounds of the museum, I am confronted by a huge stone archway inscribed with the words of the prophet Ezekiel from this same chapter 37, our reading for today: “I will put my Spirit into you and you shall live again and I will set you upon your own soil.” Contemplating this inscription, I was rooted to the spot. We had been in Jerusalem and the West Bank for four days. I was not feeling close to the redemptive Zionist dream.

Walking through the museum, I traversed the whole, familiar story: from the laws enacted in the thirties, the walls of isolation, privation, and degradation closing in, to the Final Solution: the ovens, the stacked bodies, the faces of the children. I felt I might never escape from this horror, this pit of evil and despair. And then, suddenly, ascending a wide flight of stairs, I was outside, in the light and the open air, standing on a wide patio that looked out on the Jerusalem Hills. Again, I was rooted to the spot: This, I realized, was the final exhibit.

From the promise inscribed on the archway, through the suffering of all our long history, we had reached The reward. Our destiny. Our birthright. And here is the tragic irony – as you stand on that patio and gaze out on these hills, you are looking at the ruins of Deir Yassin, a defenseless Palestinian village where over 100 men women and children were massacred by Jewish forces in 1948 .

Dry bones indeed!

Can these bones live? Shall we recognize that this is our Jewish narrative today, the story of what we have done to an indigenous population, an entire culture, in pursuit of our own redemption?

Can these bones live? Can we look in the mirror, see how far into sin we have fallen, see that it is not too late to create a society worth living in, a Jewish community in historic Palestine that is sustainable and legitimate, a society that expresses the real values of our faith and our history? Can this spirit visit us, tongues of fire that enable us to speak this universal language, the fire of the Spirit that will open us to the suffering of those we have wronged, that can bring down the walls of exclusivity and privilege?

Can these bones live?

I know that what I am saying here has come to be politically incorrect in an interfaith context. Because of the very appropriate Christian horror and shame about anti-Semitism, and the very important need to disavow replacement theology and Christian triumphalism, Christians have come to believe that they can’t say anything that could even suggest that Christianity brought something new, that it took forward the magisterial social justice tradition of the Torah and prophets, took it in a direction that it needed to go and was meant to go. But it did, and it is this:

The gospels record Jesus in the company of his disciples standing before the Temple the day they entered Jerusalem. The disciples, simple Galileans, are very impressed by the huge stones and massive buildings. But Jesus says to them, “Destroy this Temple and in three days I will raise it up.” And the disciples, again typically, are completely confused by Jesus’ startling statement. Master they say, they have been building this for 46 years, how can you build it up in three! As usual, they don’t get it. But the narrator explains, just to make sure that we get it: “He was speaking of the temple of his body.” Body of Christ: one humanity united in one communion. From empire and domination, to the equal sharing of God’s bounty in justice and compassion. This Temple and all it represents – the one percent oppressing and impoverishing the 99 percent – is gone – transformed into my Kingdom on earth.

Talk about Good News!

The church is called. The church has done it before, the church can do it again.

We recall the central role of the church in the Civil Rights movement in America, when the courage of African-American pastors changed the political and social landscape of America, articulating a philosophy of nonviolent direct action that was an explicit evocation of the sacrificial spirit of the early church, when Christians were proud to be identified as troublemakers. We lift up the example of the South African church when, declaring its Kairos in the 1985 document “Challenge to the Church,” it summoned the church to speak and act against the evil of Apartheid, challenging the very church theology that had supported the racist system. And in our day the Palestinian churches have issued their Kairos statement, a call to the churches of the world entitled “A Moment of Truth: A cry of faith, hope and love from the heart of Palestinian Suffering.”

Tongues of fire, indeed! Can these stones live?

The church is, once again, as it is always, called to read the signs of the times, to recognize that this is the favorable time, the moment of Grace and Opportunity, when, in the words of the South African Kairos Document, God issues a challenge to decisive action.

Can the church respond to this challenge? Can the church be the church? Can these bones live?

The answer is yes. That is its nature. “The church,” wrote George MacLeod, “is a movement, not a meetinghouse.”

Can these bones live? Shall the church claim its heritage, understand what power we humans receive when we are open to the coming upon us of the Holy Spirit?

Can these bones live? Can we stand up, renewed, sinew, flesh and bone, a multitude speaking the universal language of justice, as the Spirit gives us the ability?

This the clear and simple message of Pentecost. This is the story of that day. This is the story we have come to this place of worship today on this island to tell. This is the story and the Spirit to which this community has been devoted since its founding in the 1930s and indeed since its original founding over 1400 hundred years ago, as the tradition has it, on Pentecost.

In closing, I would like to bring to mind the events that led to that Pentecost of long ago, the day Jesus entered Jerusalem. He was accompanied by a crowd of Jews, suffering horribly under the tyranny of Rome, who were joyfully (and noisily) celebrating the message and ministry of a leader who offered them dignity and hope in the darkest times.

The Gospel of Luke records:

“As Jesus was approaching the path down from the Mount of Olives, the whole multitude of the disciples began to praise God joyfully with a loud voice for all the deeds of power that they had seen, saying ‘Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord! Peace in heaven, and glory in the highest heaven!’”

The local authorities were displeased. Your singing and praising and proclaiming, they told Jesus, threatened to disrupt the establish order, to spoil the accommodation they had made with the Empire. “‘Teacher,’ they said to him, ‘order your disciples to stop!’ He answered, ‘I tell you, if these were silent, the very stones would shout out!’”

Whether praise or protest, you cannot silence the cry of the oppressed nor deny the hunger for justice. And what was all the noise about, after all? It was the spontaneous response of an oppressed, occupied people—a cry of love, adoration and sheer joy for the miracle of Jesus’ ministry—his power to heal, to inspire, to lead. You can’t stop this! Jesus was saying. Nature itself, even these seeming inert stones, resonates with the joy and life force emanating from the people.

My sisters and brothers, the time has come for us to do some shouting. The times challenge us to remain true to the principles that lie at the heart of our civilization and our faith traditions. In these urgent, prophetic times, let us remember the shouting. God loves that shouting.

Let us pray.

Compassionate God,

Sometimes we feel dried up. We lose our hope, we cut ourselves off from the source of true power. Help us to receive the power of your Spirit, raise us to our feet so that we can stand, a multitude filled indeed with the new wine of prophecy. Let us remember the shouting of joy and praise of those seekers of justice, from long ago and in our own day. The times call us to discipleship, now as it was then, now as ever to receive the power and the fire of the Holy Spirit. Grant this in the many names you are called, to all who suffer oppression, and all who work for peace, and to us today in this place.

Amen