Footnotes in Gaza — The Power of Memory

My review of Joe Sacco’s astonishing Footnotes in Gaza appeared in Commonweal Magazine in October, 2011. It was a powerful experience for me to turn to it again today. The brilliance of the book is how it takes us back to ’48, then to the near unknown (outside of Gaza) events of ’56, and how these resonate so horribly and bloodily in present time. “Present time” for Sacco, of course, and for me when I wrote the book, was the Cast Lead massacre of 2008-2009. In 2014 the power of memory grows in power and urgency (viz. previous blog posting, which should have been titled, “We’ve arrived at the “G word.” I recommend this book.

Review: Footnotes in Gaza, by Joe Sacco, Metropolitan Books, 2009

Mark Braverman

The Power of Memory

The graphic novel has emerged from its expanded comic book, detective thriller and pulp fiction origins to become a powerful literary form. Belying its name, the form has been applied to great effect as nonfiction, particularly in current affairs and history. Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1986 part 1, 1991 Part 2) immediately comes to mind, in which the author describes his father’s experience as a Holocaust victim and survivor, and Marjane Satrapi’s 2003 Persepolis, the story of the author’s growing up in modern Iran. Through two previous books (Safe Area Gorazde, 2000, and Palestine, 2001) Joe Sacco has established himself as a master of the genre. Footnotes in Gaza charts Sacco’s visit to Gaza in 2002-2003 to investigate two massacres of Palestinians that occurred in November 1956. The killings, carried out by Israeli troops during their occupation of Gaza for a brief period during the Suez crisis, took the lives of 275 unarmed Palestinian civilians in the towns of Khan Yunis and Rafah, according to United Nations figures. The events drew little international attention and were largely forgotten except by the members of the communities in which they occurred.

The majority of the residents of these towns are refugees – the descendants of the 200,000 Palestinians driven from their farms, villages and cities by Jewish forces during the campaign to establish the State of Israel between 1947 and 1949. The teeming cities that Sacco visited in 2003 and that the Israeli troops encountered in 1956 are effectively refugee camps — eighty five percent of Gaza’s total population of 1.5 million is comprised of the descendants of these original refugees. This historical background is the heart of Sacco’s story. Early in the book he provides a brief, stunning picture of the early history of these people – refugees from their villages and farms, lands now in the hands of the Israelis – people banished to tent camps in the sands of Gaza, “landless, destitute, hungry; dependent on meager handouts.”

William Faulkner famously wrote: “The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past.” In Footnotes in Gaza the pictures of Khan Younis and Rafah in 1948 as silent, primitive encampments alternate with the present scene of humming, crowded cities bursting at the seams with restless energy and seething rage. Sacco shows us the quiet, grinding desperation of the families attempting to carry on under occupation and the late-night gatherings of aging, exhausted freedom fighters and frustrated, unemployed young men. And always, everywhere, there are the memories — of the dispossession, the humiliation, the helplessness, the losses — and the ineradicable hope of return, if not to the vanished villages themselves, then to a condition of dignity, visibility, an uncomplicated sense that we are allowed to be.

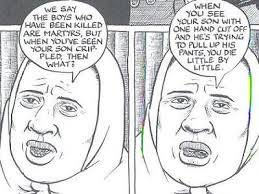

A woman on a streetcorner, surrounded by children, watching the demolition of her neighborhood by Israeli bulldozers, assails Sacco with the question, “What’s all this little by little? Why don’t they get rid of us in one go?” It is not just her home and her memories that are being destroyed – her very future is at stake. Her son, shards of shrapnel embedded in his head, is down the street, throwing stones at the bulldozer. “Can’t you stop him?” asks Sacco. “You can’t stop them!” she screams. “The blood of the Intifada is in the boys!” Reading this, I thought of Fawzieh al-Kurd, the matriarch of one of the Palestinian families forcibly expelled from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem in 2009 to make way for Jewish settlers. I met her 6 months ago, shortly after her expulsion, sitting with her in the flimsy tent she had set up outside the house as a self-imposed protest against this outrage. With profound sorrow, Fawzieh told me the story of her grandson, who dreamed of being a pilot so that he could “bomb the Jews.” This woman had taken in stride the theft of her home and the assault on her dignity — what she mourned was the loss of the future. When the children are lost to hatred, then hope is shattered, despair lurks.

A woman on a streetcorner, surrounded by children, watching the demolition of her neighborhood by Israeli bulldozers, assails Sacco with the question, “What’s all this little by little? Why don’t they get rid of us in one go?” It is not just her home and her memories that are being destroyed – her very future is at stake. Her son, shards of shrapnel embedded in his head, is down the street, throwing stones at the bulldozer. “Can’t you stop him?” asks Sacco. “You can’t stop them!” she screams. “The blood of the Intifada is in the boys!” Reading this, I thought of Fawzieh al-Kurd, the matriarch of one of the Palestinian families forcibly expelled from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem in 2009 to make way for Jewish settlers. I met her 6 months ago, shortly after her expulsion, sitting with her in the flimsy tent she had set up outside the house as a self-imposed protest against this outrage. With profound sorrow, Fawzieh told me the story of her grandson, who dreamed of being a pilot so that he could “bomb the Jews.” This woman had taken in stride the theft of her home and the assault on her dignity — what she mourned was the loss of the future. When the children are lost to hatred, then hope is shattered, despair lurks.

The book feels too long. One loses track of the characters — the story line rambles and doubles back on itself. For the reader, unfamiliar with the tragic history of this sliver of land, it’s confusing. Many of Sacco’s interviewees can no longer sort out when a particular death or violent incursion occurred – was it ‘52? ‘56? But this is the bitter experience of those who live it, who, despite their suffering, expect a story line for their lives, who expect, for themselves and their children, a sense of continuity and some kind of progress. Instead, life is a crushing, heartbreaking doubling back on the past. In this, Sacco’s book resembles Elias Khouri’s magnificent 1998 (English translation 2006) Gate of the Sun. Khouri’s characters are the Palestinian villagers driven from their homes in the Galilee between 1947 and 1949, who fled, mostly north to Lebanon, to live in the open and in temporary shelter in villages and towns. Until 1952, when the great majority of the refugees were settled permanently in refugee camps in Lebanon, many continued to attempt to return to their homes in Palestine under threat of being captured or killed by Israeli forces. Like Footnotes in Gaza, Khouri’s book is about what happens to identity when place is upended—what happens when the ground upon which you raised your children and brought bread and fruit from the earth is taken away by force. For Khouri’s fictional characters, like Sacco’s Gazans, memory suffers, truth and legend blur. Fantasies, dreams, memories, and desire swirl dizzyingly in search for a sense of self and community in the unending cycle of military invasion, economic deprivation, and political anomie.

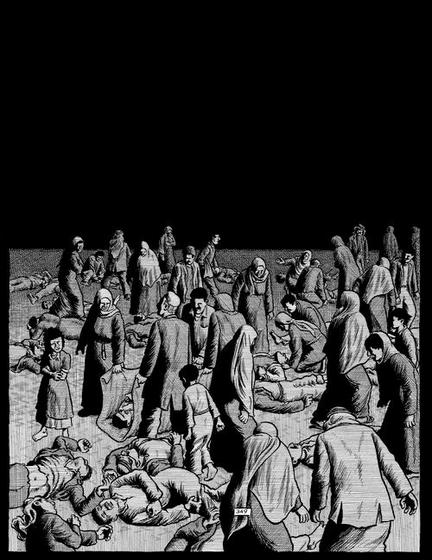

Footnotes in Gaza is awash in blood and in the sounds of machine gun fire and the thud of clubs on heads, backs and shoulders.  Women drag their slaughtered men from the street for hurried burial in mass graves. In unearthing these memories Sacco seeks to understand and thus break the cycle of violence. An enduring settlement to the conflict depends on first acknowledging the profound injuries suffered by these people, and then by granting self determination and full human rights to the inhabitants of Gaza. Nothing short of that will work. Yes, in 2005 Israel emptied Gaza of illegal Jewish colonies, but Gaza’s people remain prisoners in their own land. It is a place, in the words of Jonathan Ben Artzi, an Israeli student, draft resister and nephew of Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, “where Israel is collectively punishing more than 1.5 million Palestinians by sealing them off in the largest open-air prison on earth.” (CSMonitor.com, 4/1/10)

Women drag their slaughtered men from the street for hurried burial in mass graves. In unearthing these memories Sacco seeks to understand and thus break the cycle of violence. An enduring settlement to the conflict depends on first acknowledging the profound injuries suffered by these people, and then by granting self determination and full human rights to the inhabitants of Gaza. Nothing short of that will work. Yes, in 2005 Israel emptied Gaza of illegal Jewish colonies, but Gaza’s people remain prisoners in their own land. It is a place, in the words of Jonathan Ben Artzi, an Israeli student, draft resister and nephew of Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, “where Israel is collectively punishing more than 1.5 million Palestinians by sealing them off in the largest open-air prison on earth.” (CSMonitor.com, 4/1/10)

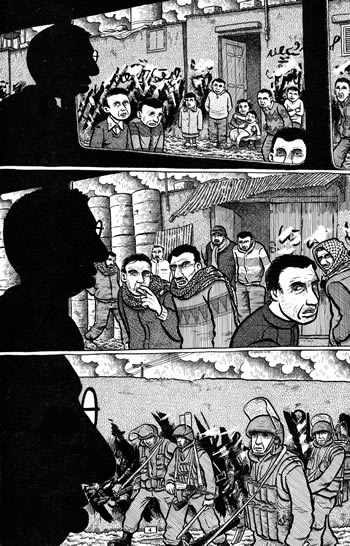

Why has peace been so elusive? The eyes that look out from the pages of Footnotes in Gaza provide the answer. Those of the Palestinians are haunted, terrified, angry, and tired (and sometimes laughing – the humor, sometimes black, is a constant subtext). Those of the Israelis, when you see them — often the eyes are averted, and few are show close up – are empty. If the Palestinians are represented by their eyes, then the Israelis are most often drawn as simple extensions of the gun, the club, the uniform. With few exceptions, the Israelis depicted in the book are lost in their lust for territory and security, preoccupied with fighting what they see only as an implacable enemy. The humanity has been blasted out of them. It is very clear that they do not see the Palestinians as people or care about their suffering.

Does Sacco in this reveal an “anti-Israel” bias? Has he created a one-dimensional, monstrous caricature of the Israeli conqueror? As a Jewish American, born in 1948 and raised on the Zionist romance, and now in grief over the pass that my people has come to, I find Sacco’s depiction compassionate in the deepest sense. I have seen the deadened look in the eyes of the Israeli army kids staffing the checkpoints throughout the West Bank — the sons, daughters and grandchildren of my own family and friends. I have seen the effects of the soul-killing racism that has taken root in Israelis society, fed by a steady diet of fear and above all by the failure of the Israelis to know their Palestinian neighbors. If my fellow Jews reading this book squirm at this picture, this is understandable. But Sacco is holding up a mirror to us – we are looking at what our national homeland project has brought us to, and well might we squirm.

Does Sacco in this reveal an “anti-Israel” bias? Has he created a one-dimensional, monstrous caricature of the Israeli conqueror? As a Jewish American, born in 1948 and raised on the Zionist romance, and now in grief over the pass that my people has come to, I find Sacco’s depiction compassionate in the deepest sense. I have seen the deadened look in the eyes of the Israeli army kids staffing the checkpoints throughout the West Bank — the sons, daughters and grandchildren of my own family and friends. I have seen the effects of the soul-killing racism that has taken root in Israelis society, fed by a steady diet of fear and above all by the failure of the Israelis to know their Palestinian neighbors. If my fellow Jews reading this book squirm at this picture, this is understandable. But Sacco is holding up a mirror to us – we are looking at what our national homeland project has brought us to, and well might we squirm.

Footnotes in Gaza is the story of today’s Palestine. It explains the roots of Palestinian resistance. It thrusts the moral, psychological, political and spiritual crisis facing the State of Israel and indeed the Jewish people into the light of day. It calls on Americans to grasp the central responsibility of our government in its unconditional financing of Israel’s expansionist military machine and its diplomatic defense of Israel in the international arena.

In his foreword, Sacco explains that he wrote the book because he found the editor’s deletion of the story of the Khan Younis massacre from Chris Hedges’ 2001 “A Gaza Diary” in Harpers (on which Sacco had collaborated) “galling.” As a journalist, he felt compelled to write about it because he felt that such tragedies “often contain the seeds of the grief and anger that shape present-day events.” And this is true, but not just for the Palestinians. Today, events in Palestine take place in the huge shadow cast by the Nazi holocaust. None regard that catastrophe as a footnote — it is acknowledged to have shaped modern history, including the lives and destinies of the Palestinians who people this book. The consignment of the dispossession and suffering of the Palestinians to a historical footnote, in stark contrast to the elevation of the suffering of the Jewish people, is a key element of the story told here. And it is a key to solving the dilemma of how to make peace in historic Palestine.

During the brutal bombardment of Gaza in January 2009, Sara Roy, a prophetic American Jewish voice, wrote the following:

What will happen to the Jews as a people, whether we live in Israel or not? Why have we not been able to accept the fundamental humanity of Palestinians and include them within our moral boundaries? Rather, we reject any human connection with the people we are oppressing. Ultimately, our goal is to tribalize pain, narrowing the scope of human suffering to ourselves alone. (“Israel’s ‘Victories in Gaza Come at a Steep Price,” Christian Science Monitor, 1/2/2009)

This is a question not just for the Jewish people. Sacco has given us a book about the universality of suffering and a powerful lesson about the power of memory for repentance and repair. We ignore it at our peril.